| Audio visual content being loaded on to touchscreens. |

|

| The display is located near the front entrance of Leeds City Museum |

A little tweaking to do, but the display is ready for visitors now. This display complements the displays at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich (part of the National Maritime Museum) that are dedicated to navigation, precision timekeeping and John Harrison. It is the only display outside of London about John Harrison, and, by chance, is near to his birthplace, Foulby, Wakefield. Harrison's magnificent contribution to advancing precision timekeeping cannot be overstated, equally so its significance. It not only advanced navigation science, and map making, but has also had profound effects on engineering and technology. Harrison was an autodidact, his was an intellectual journey to achieve precision timekeeping as a means of finding longitude at sea, the lack of such means being a huge problem for mariners on their journeys. Pervasive throughout cultures around the world, in art, literature, poetry, music, film and faiths, are references to journeys and navigation, to time and stars. The star of Bethlehem, guiding the three kings on their journey for example, or Eccesliastes 3:1, "There is a time for everything, and a season for every activity under the heavens". Or in literature, fiction, and non-fiction equally, from Peter Pan, and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, to the biographies of great people like Albert Einstein, Captain James Cook, or Charles Darwin, and the voyage of the Beagle, the putative beginning of Darwin's long thinking and reflection that led to the great truth he discerned, The Origin of Species. Whenever I have encountered them, these references, they have stood out to me.

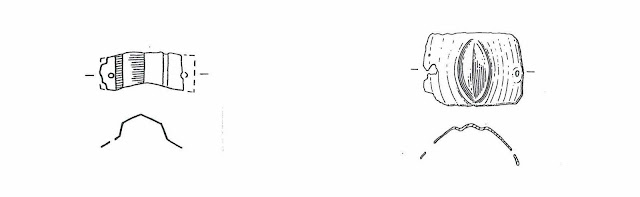

Harrison precision pendulum clock No. 2, from the collections of Leeds Museums and Galleries, the object at the core of the display.

Second star to the right, and straight on 'til morning, keep on trekking!

"Location aware music" contemporary performance art and GPS combined, in a great example of the human drive to create beauty, and seek moments of awe, and using new technologies to serve this human need.

"Location aware music" contemporary performance art and GPS combined, in a great example of the human drive to create beauty, and seek moments of awe, and using new technologies to serve this human need.

Sidereal time is the time scale that is based on the Earth's rate of rotation measured relative to the fixed stars. This is a technique that was known and used by John Harrison in regulating his timekeepers. "All men have stars, but they are not the same things for different people. For some, who are travelers, the stars are guides…."

John Harrison advanced precision timekeeping, by mechanical means, by an amount that had not been seen before or since. Today the time standard is kept by atomic clocks, that in a sense are gauging the entropy of the universe. We can understand what timekeeping is, but what is time itself? Perhaps the best explanation is the concept of the arrow of time. Albert Einstein's special theory of relativity also goes some way, perhaps, of explaining what spacetime is. Einstein also had a very good sense of humour: “When you are courting a nice girl, an hour seems like a second. When you sit on a red-hot cinder, a second seems like an hour. That's relativity.” This much is certain: time is a precious resource, not to be wasted, crack on, like smoke and oakum.

John Harrison advanced precision timekeeping, by mechanical means, by an amount that had not been seen before or since. Today the time standard is kept by atomic clocks, that in a sense are gauging the entropy of the universe. We can understand what timekeeping is, but what is time itself? Perhaps the best explanation is the concept of the arrow of time. Albert Einstein's special theory of relativity also goes some way, perhaps, of explaining what spacetime is. Einstein also had a very good sense of humour: “When you are courting a nice girl, an hour seems like a second. When you sit on a red-hot cinder, a second seems like an hour. That's relativity.” This much is certain: time is a precious resource, not to be wasted, crack on, like smoke and oakum.

Sea Fever

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by;

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face, and a grey dawn breaking,

I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide

Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied;

And all I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying,

And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying.

I must go down to the seas again, to the vagrant gypsy life,

To the gull’s way and the whale’s way where the wind’s like a whetted knife;

And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow-rover,

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick’s over.

The hard opening of the display was on 23/01/2014, and was marked with a very fine lecture, to an audience of nearly 180, by Dr Richard Dunn, Senior Curator, Science, Technology and Navigation, from the National Maritime Museum.

Blog of the Board of Longitude project "Leeds leads"

Posted by Ian Fraser

Blog of the Board of Longitude project "Leeds leads"

Posted by Ian Fraser